Education is often imagined as a traditional classroom—rows of desks, chalkboards, and textbooks. Yet, beyond these familiar walls, there exist extraordinary institutions redefining what learning can be. Around the world, innovative schools are transforming education through creative environments, unusual teaching philosophies, and community-led experimentation. From classrooms floating on rivers to forest schools under the open sky, from technology-free campuses to academies for circus arts and mountaineering, these remarkable places prove that learning has no boundaries.

“Unique Schools Around the World”, invites readers on a journey across continents to explore how different cultures shape education and prepare children for life in unconventional ways. Each story highlights the purpose, philosophy, student experience, and the lessons we can adopt to improve our own educational systems. Through these inspiring examples, we discover that there is no single formula for learning—only a commitment to imagination, resilience, and human potential.

Forest School — Learning Without Walls

What is a Forest School?

- Forest School is a child-centred, outdoor-based approach to education: instead of traditional classrooms, children learn in woodlands, natural settings or other outdoor environments.

- The approach emphasizes hands-on learning, exploration, creativity, play, and learner-led discovery rather than strict lesson plans or rote learning.

- It aims for holistic development — not just academic skills, but social, emotional, physical, environmental awareness and self-confidence.

Origins: Where and Why Forest Schools Began

- The idea has its roots in the 1950s Scandinavia — specifically Denmark, Sweden and later other Nordic countries — where “open-air living” and close connection with nature were already part of cultural tradition.

- In Denmark, the earliest known “forest kindergartens” started with informal gatherings of children playing outdoors (around 1952), driven by parents wanting a healthy, nature-rich environment for their children.

- In Sweden, a programme called Skogsmulle (est. 1957) used storytelling, nature-based play and exploration to build children’s love for nature.

Over time, this grew from informal playgroups into formal “forest kindergartens” and “forest schools,” and has spread beyond Scandinavia to many parts of Europe, the UK, North America and elsewhere.

What Happens in a Forest School: Daily Life & Activities

- Instead of sitting at desks, children climb trees, build shelters with branches, whittle wood, light small fires (under supervision), identify plants and insects, observe wildlife — all while under the supervision of trained facilitators/practitioners.

- Learning is often unstructured and guided by the children’s curiosity — if a child is interested in insects under a rock, that becomes the subject to explore: examine soil, biology, ecology, decomposition — blending science, environmental learning, and direct experience.

- Sessions are regular and long-term (not just one-off trips). Frequent exposure to natural environments helps children build a sense of comfort, resilience, and deeper connection with nature.

- Importantly, such learning supports risk-taking in a safe environment — planning, building, evaluating, working in groups — helping children gain confidence, independence and practical life skills.

Benefits & What Research Says

According to educators and studies:

- Children in forest schools often show better self-esteem, confidence, curiosity, creativity, teamwork and social skills compared to traditional schooling environments.

- Outdoor, nature-based learning helps in physical development, motor skills, spatial awareness, and encourages imagination, problem-solving, and autonomy.

- For some children — especially those who struggle in conventional classrooms, or have behavioural difficulties — Forest School offers a constructive environment where they can thrive, feel safe and find their own pace.

- Exposure to nature also fosters environmental awareness and respect for nature, helping children understand the interconnections between living beings, nature cycles and their own role in the world.

Why It Matters — What It Can Teach Us

- Forest School challenges the traditional idea of education as confined to buildings and textbooks: it shows learning doesn’t need walls — life experience, nature, curiosity

- and exploration can be powerful teachers.

- In a world facing environmental degradation, rapid urbanization and disconnected childhoods, this model reconnects children with nature, ecology, and community — fostering respect and care for the environment from a young age.

- It encourages holistic development — blending physical, social, emotional, cognitive skills — which is often missing in standard curricula focused mainly on academics/exams.

- The approach is flexible: while ideal in woodland settings, it can adapt to local natural environments — parks, open spaces, school gardens — making it potentially applicable even outside traditional “forest-rich” countries.

Reflection: Would Forest School Work in India

Given India’s rich variety of natural environments — forests, rural landscapes, hills, fields — the Forest School idea could be adapted here too. Even in towns, a school-garden or urban-park based “outdoor classroom” could bring many benefits: improved health, environmental awareness, physical activity, hands-on learning beyond books.

Challenges might include safety, weather and infrastructure, but with committed educators/parents and adaptation to local conditions (seasonal changes, cultural relevance), a version of Forest School could become a powerful alternative to conventional schooling.

Floating/Boat Schools — Education That Floats

What is a Floating or Boat School?

- A floating school (or “boat-school”) is a mobile educational setup built on a boat — acting as both school bus and classroom.

- These schools are designed to serve children living in flood-prone, waterlogged or riverine regions, where conventional land-based schools are often inaccessible or impossible during monsoons or seasonal floods.

- Rather than the children going to school, the school comes to them: boats travel from riverside village to village, collecting students and delivering education directly on water.

Where — and Why — Floating Schools Exist

- Floating/boat schools are prominent in certain flood-prone regions of Bangladesh, especially in the “haor” (wetland) areas, deltas, river-basins — places where frequent flooding disrupts road access and makes standard schooling unreliable.

- The initiative was started by Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha (SSS), a non-profit organisation that launched its first floating-school boat back in early 2000s under the guidance of social-entrepreneur Mohammed Rezwan.

- This model recognizes that for many rural water-bound villages, children previously had little or no access to formal education — the boat school offers access, continuity and hope.

How Boat Schools Work — Day to Day & Their Design

- Each “school-boat” is built or converted to serve as a classroom, often equipped with benches/desks, a small library or bookshelf, educational materials, and — in many cases — even solar-powered electricity, lighting and basic computing/learning aids.

- Boats follow a schedule: they collect children from different riverside villages (halts at ghats/piers), then move or stay docked for classes. After teaching, students are dropped back home by boat.

- The curriculum typically covers primary education — reading, writing, basic arithmetic, etc. Some boat-school programmes also teach environmental awareness (especially water-conservation, river ecology), reflecting the local conditions.

- Beyond schooling: in many instances, the same boat-infrastructure doubles up as a community resource — functioning as floating libraries, vocational-training centers, or even health-clinics during extreme floods.

Impact — Why Floating Schools Matter

- For many children in remote, flood-prone areas — previously excluded from education — boat schools have opened the door to literacy and opportunity.

- Studies and reports show that these boat schools help reduce dropout rates, increase primary education completion, and give hope where conventional infrastructure fails.

- The model is celebrated globally as a social-innovation: combining education, climate-resilience (flood adaptation), renewable energy (solar boats), community outreach (libraries, adult learning) — adapting schooling to environmental realities rather than forcing children into inaccessible buildings.

- For many families, this school-on-water has broader social impact — empowering children (often first-generation learners), especially enabling girls to attend school in places where safety or long commutes would otherwise prevent it.

What Makes It “Unique School” Material

- This is not just a different building — it’s a mobile, adaptive, environment-responsive school: when floods rise and land disappears, learning doesn’t stop — the school floats.

- It combines education with climate- and socio-economic resilience: addressing not only learning gap but also tackling isolation, accessibility, environmental challenges with a culturally-sensitive, low-cost solution.

- It’s a community-driven, local-resource rooted model — built with local boat-building traditions, solar power, locally available materials, operated by local NGOs/organizations — demonstrating sustainable, scalable design for rural, under-served regions.

- It challenges the notion that schools must be fixed brick-and-mortar institutions — showing that with innovation, education can be brought to even the most remote, water-locked communities.

Could This Model Work Elsewhere — Even in India?

Given parts of India (especially flood-prone regions near rivers, wetlands, deltas — like Assam, Bengal, parts of Bihar) face similar geographical/environmental constraints, a “floating-school” style model — adapted to local conditions — could offer hope:

- It could reach children in areas where seasonal floods, poor roads or remoteness make schooling difficult.

- It could combine education with local livelihood training, environmental awareness (especially about water, climate, ecology).

- It would need careful adaptation: boat-design for safety, local governance, community buy-in, trained teachers, basic resources — but conceptually, the model is promising and socially relevant.

Green School Bali — School for Sustainability & Nature-Immersive Education

What is Green School Bali?

- Green School Bali is a progressive PreK–12 school located in the jungle near Ubud, Bali — but it’s not a “regular school.” It’s built around sustainability, nature, community and a belief in educating children for a more sustainable future.

- Its campus is almost entirely made from natural, renewable materials (especially bamboo), and the classrooms are open — often without conventional walls — blending indoor/outdoor space and immersing students in a jungle-environment.

Why It’s Unique: Philosophy & Design

- The core philosophy is “living curriculum”: learning through real-world, hands-on experiences — not just textbooks. Students learn sustainability, ecology, agriculture, renewable energy, community responsibility, and design thinking in their everyday school life.

- The campus itself is part of the learning: sustainable bamboo architecture, solar power, micro-hydro power, permaculture gardens, composting systems, aquaponics — everything around the school becomes a teaching resource about ecology, sustainability, and responsible living.

- Students don’t just study about sustainability — they live it. From growing food to renewable energy projects to designing sustainable transport — school projects are aimed at real impact, not hypothetical lessons.

Curriculum & Student Life

- Education at Green School blends academic basics (literacy, mathematics, sciences) with sustainability-oriented courses: environmental science, agriculture, social entrepreneurship, design & innovation, community engagement, arts.

- Learning is holistic — focusing on intellectual, emotional, social, ecological growth. Students often work collaboratively on long-term projects: e.g. planting & harvesting crops, restoring ecosystems, building sustainable solutions.

- Extracurricular / community-oriented: The school encourages social entrepreneurship, sustainability activism, and community outreach. For example, students set up a “BioBus” — a bus running on biodiesel made from used cooking oil — to promote green transport in their community.

Impact & Recognition

- Green School Bali has gained global recognition as a pioneering example of what education can be when aligned with sustainability and environmental ethics.

- It has inspired similar “green school” efforts worldwide.

- Graduates from Green School often emerge as socially-conscious, environmentally-aware “changemakers,” equipped with both academic knowledge and real-world skills to contribute to sustainable communities.

What We Can Learn — Relevance to Other Contexts

- Education need not be confined to concrete buildings and traditional classrooms: blending with nature can foster stronger environmental awareness, creativity, and holistic growth.

- A school can be a micro-community that teaches responsibility, sustainability, social entrepreneurship — preparing students not only academically but ethically and socially for modern global challenges.

- Even if full replication is difficult (bamboo buildings, jungle campuses), many principles — sustainability curricula, hands-on learning, community engagement — can be adapted to local schools, including in India, to nurture socially conscious future generations.

Waldorf / Steiner Education

- Waldorf Education was founded by Rudolf Steiner in 1919, starting with the first school in Stuttgart, Germany.

- Today it is one of the largest independent school movements globally — with over 1,200 Waldorf schools and nearly 2,000 early-childhood (kindergarten) programs across many countries.

- The aim is holistic education: developing children not just academically, but intellectually, emotionally, practically, artistically and socially — “head, heart, and hands.”

Philosophy & Educational Approach: What Makes It Unique

- In Waldorf/Steiner education, creativity, art, music, movement, crafts are integrated into all subjects — not treated as separate “extras.” This helps children develop imagination, aesthetic sensibility, emotional intelligence along with academic skills.

- The curriculum is age-appropriate and stage-based: early childhood emphasizes play, stories, movement; middle childhood mixes arts with academics; adolescence focuses on independent thinking, deeper learning, moral and social responsibility.

- Emphasis on experiential learning: children are encouraged to learn by doing — crafts, projects, hands-on work — not just by memorizing from books.

- Assessment is typically non-standardized (not heavy on frequent exams/tests)— instead growth is tracked via teacher observation, individual progress, and a more qualitative understanding of student development.

Typical Day / What Student Life Looks Like (Compared to Traditional School)

- Rather than focusing only on academic drills, a day might include storytelling, music, drawing/painting, crafts, drama, movement — integrated with academic learning.

- The environment is often more calm, nurturing, emotionally safe; the community (teachers, parents) tends to value individuality — helping each child grow at their own pace.

- Education balances intellectual development with practical skills, social awareness, creativity, moral sense — aiming to shape well-rounded individuals, not just high test-scorers.

- There is often a sense of continuity and relationship-building: in many Waldorf schools, the same teacher may stay with a class for several years (especially in early grades), strengthening trust and understanding.

Global Spread & Variations

- Waldorf/Steiner schools are found all around the world — in Europe, Americas, Asia, Africa — adapting the core philosophy to different cultural and social contexts.

- For example, in India there is a school following this approach: Inodai Waldorf School, Mumbai — which combines academic learning with arts, crafts, drama, creativity and holistic growth.

- Because Waldorf emphasizes creativity and flexibility over standardization, each school may differ — but core values (holistic growth, creativity, respect for human development) remain.

What Waldorf Model Offers — Strengths & What Makes It Stand Out

- Encourages creativity, imagination, self-expression, emotional intelligence — often lacking in exam-oriented schooling.

- Provides a child-centered, developmentally sensitive education — acknowledging that children mature at different paces.

- Helps produce well-rounded individuals — not just academically skilled, but socially aware, emotionally balanced, practically capable.

- Reduces pressure of “constant testing” — potentially lowering stress, encouraging deeper learning, love for learning rather than rote exam preparation.

- Builds community, close teacher-student relationships, holistic values — which may nurture compassion, social responsibility, and lifelong learning.

What to Keep in Mind / Challenges & Criticisms

- Because assessment is not exam-heavy, transition from Waldorf to traditional exam-based systems (e.g. board exams, competitive exams) may be difficult for some children.

- Creativity-focused approach may not suit every child — some may need more structured academic rigor or traditional subject-by-subject discipline.

- Peer comparison — in conventional schooling — may be harder to gauge, and parents may worry about “academic competitiveness” or standardization.

- As with any holistic/alternative system, success depends heavily on quality of teachers, their commitment, and alignment of school values with child/parents.

What We Can Learn — Could Waldorf/Steiner Ideas Work in India?

Given India’s rich cultural diversity, arts, crafts heritage, and varied childhood experiences — a Waldorf-inspired school could:

- Nurture creative, emotionally aware, socially responsible youth rather than exam-driven students.

- Offer children balanced growth — academic + artistic + social + emotional — which may reduce stress and encourage love for learning.

- Be especially beneficial in early childhood and primary education — helping children develop confidence, imagination, foundational life-skills, rather than just exam-readiness.

- Bridge traditional Indian arts, crafts, music and culture with modern education — preserving cultural richness while preparing for global challenges.

School of the Air — Education Over Airwaves for Remote Communities

What is the School of the Air

- The School of the Air is a network of distance-education programs across remote and “outback” regions of Australia — designed for children living so far from conventional schools that regular daily schooling is not feasible.

- Instead of a brick-and-mortar classroom, students attend lessons from their homes, remote stations, or family properties. Historically, education was delivered over two-way radio waves; now it primarily uses satellite technology, internet video-conferencing and interactive digital tools.

Why and Where It Began

- The model originated because many children live scattered across vast, sparsely populated areas — long distances from the nearest school — which makes traditional schooling impractical or impossible.

- The first official “School of the Air” opened in 1951 at Alice Springs School of the Air in central Australia, inspired by efforts of the medical-service network Royal Flying Doctor Service that used radio to reach remote populations.

How It Works — Daily Life of Remote Students

- Each morning (or set teaching time), children log in from their homes via satellite-internet/video-conferencing or — previously — via radio, and attend a live class with a teacher and other remote students.

- For the rest of the day, students work independently on school assignments at home, often supervised by a parent, older sibling or tutor.

- Periodically (a few times a year), students from remote homes travel to a central school hub — a real physical location — to meet their teachers and peers and socialize face-to-face.

What Makes It Unique & Valuable

- Breaking geographical barriers: For children in extremely remote, sparsely populated areas — where building a conventional school is not viable — School of the Air offers access to quality education regardless of where they live.

- Flexibility & resilience: Weather conditions, isolation, or lack of infrastructure doesn’t block education. With satellite or internet connectivity, learning continues even in remote, harsh, or isolated settings.

- Social connection despite isolation: The school gives isolated children opportunities for peer interaction, collective learning, and community, offsetting the loneliness that remote living might bring.

- Adaptation to modern technology: The model has evolved over time — from two-way radio to satellite broadband and online video lessons — showing how education systems can adapt to reach everyone, no matter how remote.

Could This Model Inspire Education Elsewhere?

For countries or regions with remote, sparsely populated rural/tribal areas — including parts of India — a “School-of-the-Air”–style model could be a powerful alternative when physical schools are unfeasible, especially if supported by:

- Basic internet/satellite or radio connectivity

- Local tutors, parents or community volunteers to supervise home-based work

- Scheduled central meet-ups (e.g. periodic regional camps) for socialization

- Flexible curriculum adapted for remote learning

THINK Global School (Global Nomad / Travelling School)

What is THINK Global School

- THINK Global School (TGS) is a high-school (grades 11–12) where students don’t stay fixed in one country: instead, the “classroom” moves — over a two-year period, students live and study in multiple countries around the world.

- It’s a small, independent, co-educational, non-religious school, with typically small class sizes and a globally-oriented, project-based curriculum.

Why It’s Unique: Philosophy & Structure

- The core premise is “global education via mobility” — instead of learning about the world from textbooks, students live in different cultures, navigate real-world environments, and learn by immersion. This helps them build cultural awareness, adaptability, global perspective.

- Curriculum is largely project-based and place-based — meaning what students learn is tied to the country or community they’re living in that term: local history, language, environment, cultural practices become part of education.

- Students also engage in “weXplores” — cultural immersions, community projects, interactions with local people — rather than only classroom lectures.

What Student Life Looks Like

- Over two years, a batch of students might live in 6–8 different countries — each “term” is spent in a different location. That means new languages, new cultures, new environments regularly.

- Learning isn’t isolated: along with academics, students gain real-life skills — cross-cultural communication, global citizenship, adaptability, perhaps even languages — much beyond traditional curricula.

- Because class sizes are small and curriculum flexible, there is often individual attention, collaborative learning, and exposure to global issues.

What Makes It “Unique School” Material

- It breaks the assumption of a school as a fixed building/time/place — school becomes mobile and global.

- Education becomes life + travel + cultural exchange — learners don’t just read about the world, they experience it directly.

- Prepares students to be global citizens — adaptable, culturally aware, with hands-on understanding of different societies.

- Offers diversity, flexibility, and real-world perspective — contrasting with rigid exam-oriented schooling.

Relevance: Could This Model Inspire India ?

While a full-scale “travelling school” like THINK Global School may be difficult to replicate widely in India due to costs and logistics — some of its ideas could still be adapted:

- Schools could incorporate “cultural-immersion terms” — short-term exchanges or community-based learning where students spend weeks in different parts of India (rural ↔ urban), learning local culture, ecology, languages.

- Curriculum could become more project-based, experiential, real-life oriented — integrating local issues, social service, environment, crafts — instead of purely textbooks.

- Small-group learning, cross-cultural awareness — helping students become more aware, adaptable, socially conscious — useful for India’s diversity.

National Circus School — Circus / Performing-Arts School

- The Escola Nacional de Circo was established in 1982, under the aegis of the national arts authority (in Brazil), to train professional circus artists — jugglers, acrobats, performers — via a formal structured programme.

- The school offers courses in circus arts: basic 10-month “arts circus” training as well as a longer, 7-semester certificate (or diploma) in circus arts.

- Its mission is to professionalize circus arts: not just as a hobby or street-performance, but as a legitimate art form — with technical rigor, training, pedagogy, and opportunity for artists to pursue circus as a career.

What Makes It Unique & Valuable

- Mix of academia/structure + performing arts & physical skills: Instead of traditional classes, the curriculum is centered around physical training, acrobatics, performance discipline, stage-craft — integrating body, art, and discipline rather than purely intellectual/academic training.

- Serious, professional-level training for artists: The school treats circus arts professionally: long-term training, structured courses, specialization, artistic research — ensuring graduates are qualified artists, not amateurs.

- Cultural value & inclusivity: Circus traditionally draws from diverse backgrounds — students come from different states/regions, from varied social/cultural milieu — the school becomes a space where talent, not just social privilege, matters.

- Alternative to conventional academics: For children or youth who may not flourish in standard academic-focused schooling — or who have talent in performing arts — this model offers a viable path combining creativity, physical expression, discipline and livelihood.

Student Life & Training — What Happens There

- During the program, students undergo intensive training in multiple disciplines — acrobatics, dance, aerials, balancing, flexibility, coordination, performance techniques. In early phases, all students sample many disciplines; later they specialise in one or two.

- Physical conditioning and artistic training are key — many participants show body-compositions similar to high-performance athletes, because of the demands of circus arts (strength, flexibility, agility, endurance).

- The school emphasises creation and expression rather than competitive grades: for circus-performance work, “pass / continue” evaluations are used; focus remains on improving craft, expression, creativity, not only on performance metrics.

- After graduation, artists can engage professionally — in circuses, performance troupes, cultural shows, even international touring. The goal is to offer sustainable career paths in arts, not just casual performing.

Global Significance & Lessons — Why Including Circus School Matters in This Series

- Circus / performing-arts schools like Escola Nacional de Circo challenge the notion that “school = classroom + exam + desk.” They show education can be physical, creative, performative, body-based — embracing arts, talent, expression, not just academics.

- They highlight diversity of intelligences and talents: not all students are academically inclined — offering alternative pathways for creative, physical, artistic youth. This makes education more inclusive, helps preserve cultural/performing arts traditions, and recognizes varied human potential.

- They provide career alternatives beyond conventional professions — professional artists, performers, cultural workers — offering dignity to art as profession, and promoting art/culture in society.

- For societies globally — including India — this model suggests that we can value and institutionalize traditional performance arts (folk, circus, street-arts), giving formal training, dignity, and sustainable livelihoods to artists.

“Train-Platform / Street-Based Schools” — Education on Rails & Streets

- These are schools designed to reach children who live on streets, work on trains (beggars, runaway kids, homeless children), or spend much time near railway stations — places where conventional schools are inaccessible or irrelevant.

- The concept is to bring education to “hard-to-reach” children — rather than expecting them to come to a traditional school building. Classes may be held on or near train platforms, in temporary shelters or using mobile/ makeshift setups suited to the context (street, station, transit).

Why & Where It Exists

- This model often emerges in contexts where poverty, homelessness or social marginalization forces children to live/work on streets or trains — depriving them of stable homes and regular schooling. The “school-on-rails/streets” idea responds by offering flexibility and accessibility.

- According to one overview, there have been “train platform schools” in India conceived to offer basic education to children begging or living in trains — a way to reach children excluded from traditional education due to their circumstances.

- Similar “mobile” or “flexible-location” school initiatives (bus-schools, street-schools) are included in global lists of “unique schools” aiming to educate marginalized communities.

What Makes This Model Unique & Its Significance

- Reaches the most marginalized — children on streets or trains, refugees, transient or homeless children — who are often left out entirely by conventional schooling.

- Flexibility & adaptability — classes can happen where children are, at times they can attend, without requiring long-term enrolment or stable residence.

- Social justice & inclusion — an attempt to ensure even children in the harshest socio-economic conditions get basic education, literacy and hope for a better future.

- Breaking conventional assumptions about “school” — challenges the idea that schooling must always be a brick-and-mortar building; shows education can be mobile, informal, adaptive to context.

Challenges & What Needs Care

- Often such schools may have limited resources — infrastructure, trained teachers, consistent attendance — which can limit the quality or continuity of education.

- Students’ unstable living conditions (mobility, economic pressures) may make regular learning and follow-up difficult.

- Risk of dropout is high. Without stable home or community support, many children may not complete full-time education or transition to mainstream schooling.

- Social stigma and neglect — street/rail-children often face discrimination, which can hamper learning, self-esteem and opportunities.

Could This Model Be Adapted to Indian

Given India’s large population, economic disparities, and presence of many street/railway children — this model could be valuable:

- Authorities, NGOs, or community organizations could run “railway-station schools,” “street-schools,” or “bus-schools” in cities or towns where many under-privileged children stay or work.

- Education could be flexible, modular — basic literacy, numeracy, life-skills, vocational training — helping children build a foundation rather than forcing rigid curricula.

- This could serve as a bridge: from street life → education → potentially mainstream schooling, skill development or livelihood.

- With support (social workers, volunteers, trained teachers, outreach), such models could reduce child labour, homelessness effects, and create opportunities for marginalized youth.

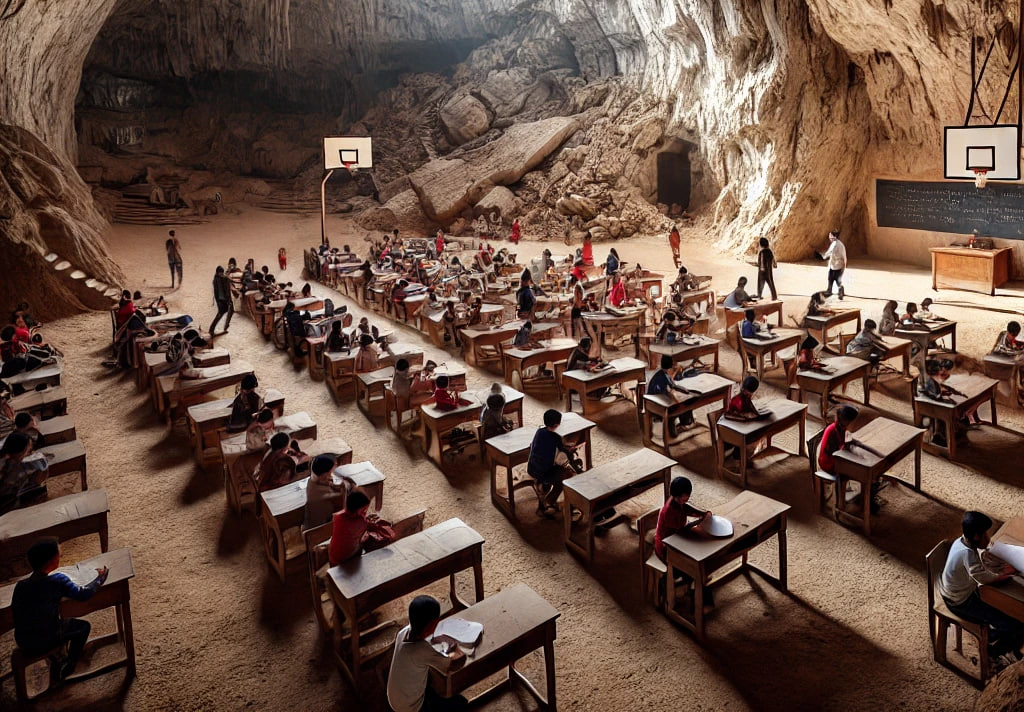

Dongzhong Cave School

- The Dongzhong Cave School was located in a remote village in Guizhou province, China — in a cave rather than a conventional building.

- The school operated with modest resources: when it opened (1984), it had 8 teachers and about 186 students.

- The cave-school was born out of necessity: the remote, impoverished and geographically difficult environment made building a conventional school nearly impossible — but the community found a natural cave to use for schooling instead.

What Makes It Unique & Why It’s “Unique School” Material

- Unexpected setting: Instead of a brick-and-mortar or wooden school building, the “classroom” is a naturally formed cave — turning a natural geological formation into a place of learning.

- Resourceful adaption: For communities with limited infrastructure — no roads, lack of funds, harsh terrain — the cave school is a creative solution: using what nature provides to ensure children still get education.

- Serving remote, marginalized communities: These are children living in remote mountainous or rural zones, far from mainstream schools — giving them access to schooling when they might otherwise be excluded.

- Symbol of resilience and hope: The fact that hundreds of children attended classes inside a cave — in challenging conditions — shows how human determination and community effort can overcome adversity and ensure education.

Challenges & What It Reveals About Limits of Such Models

- Limited infrastructure: Cave-based schools likely lack basic amenities — proper lighting, ventilation, sanitation, safety — which makes learning conditions tough.

- Fragile and temporary: Dependence on natural formations means vulnerability — caves may be unsafe, or authorities may force closure (as reportedly happened with some such schools).

- Difficult integration: Transitioning from such a school to mainstream education (higher classes, exams) can be hard due to gap in resources, curriculum limitations, lack of recognition.

- Social stigma & lack of support: Students and teachers may struggle with isolation, lack of public support, minimal funding or materials — and broader society may not give equal opportunity or prestige to such “informal” schooling setups.

What We Can Learn — Relevance for India / Rural / Remote Regions

- For remote, under-served, geographically difficult areas (hills, rural mountains, remote villages) — where building full school infrastructure is hard — community-led, resource-aware solutions (using natural spaces, caves, large huts, community centers) can help provide basic education access.

- It highlights the importance of contextual, creative solutions over “one-size-fits-all” schooling models — adapting to terrain, resources, environment and community realities.

- Such models show that education is a human right worth defending — and even under difficult physical conditions, communities may find ways to ensure children learn. For policymakers/NGOs: this can inspire “low-cost / context-sensitive” schooling for marginalized areas.

- It may help preserve local community, culture, environment-awareness — children growing up in rural/hilly areas can learn while staying connected to their environment, rather than being uprooted.